Introduction

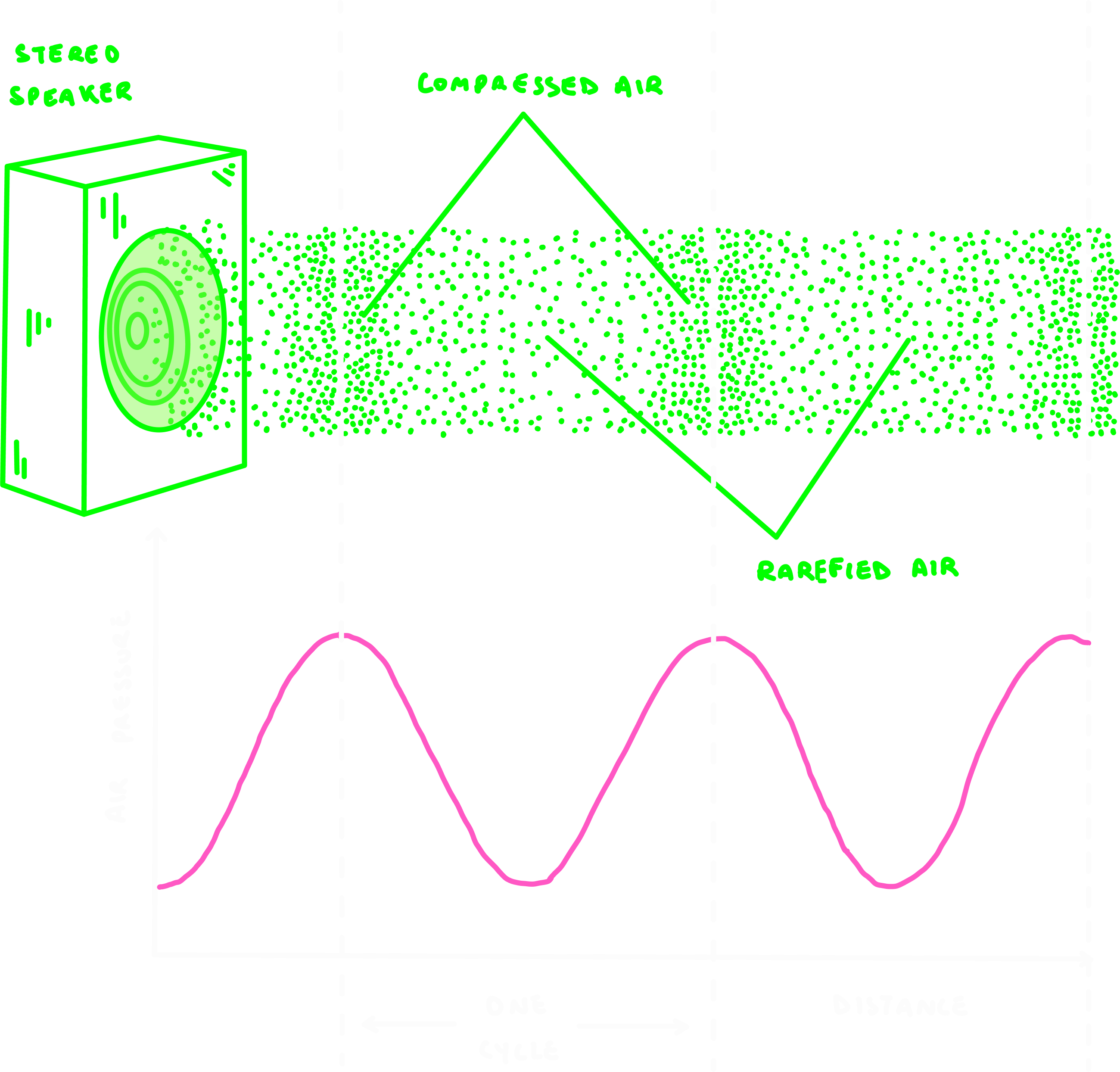

Compressed air: Regions of the wave where air molecules are closer together.

Rarefied air: Parts of the wave where air molecules are spread further apart.

There’s more pressure in compressed zones, and less pressure in rarefied zones. This alternation produces the wave-like structure of a sound wave.

A cycle is the distance between peaks or troughs of the wave.

- Pitch (frequency): Lower frequencies have more spread-out compressions and produce deeper pitches. Higher frequencies have closer compressions and create higher pitches.

- Volume (amplitude): The amplitude of the wave determines loudness — low amplitude gives us quiet sounds, high amplitude gives us loud ones.

For example, bats and dolphins detect ultrasonic frequencies above 100,000 Hz! Elephants communicate using infrasonic rumbles below 20 Hz! Wow, the range of nature <3

The simple physics of sound is only the starting point. The real marvel is how the ear, with its delicate membranes, bones, and sensory cells, transforms these air vibrations into neural signals the brain then interprets as speech, music, or environmental cues.

The Auditory System

- The Outer Ear

•Pinna: The visible part of the ear. Its curved, funnel-like shape helps capture sound waves and direct them inward.

•Auditory canal: A narrow tube that carries the waves toward the eardrum, concentrating and guiding them efficiently.

- The Middle Ear

•Eardrum (tympanic membrane): A thin, flexible membrane sitting at the end of the auditory canal. It vibrates when struck by sound waves.

•Ossicles: Three tiny bones that amplify the vibrations and pass them along. This is where air vibrations are converted into mechanical energy.

- The Inner Ear

•Cochlea: A spiral, fluid-filled structure where mechanical vibrations become fluid waves. At this point, the wave ceases to be an air/mechanical wave and becomes a fluid one.

•Auditory-vestibular nerve: Sends the information from the cochlea to the brain, where sound is recognised and interpreted.

Middle Ear

- Malleus (latin for hammer): The first place a wave is going to make contact with is our eardrum. This causes the malleus bone to start tapping/hammering on the next bone in the chain.

- Incus (latin for anvil): Receives the malleus’s force and transfers it onward.

- Stapes (latin for stirrup): Horseshoe/stirrup shaped, the stapes presses against the oval window of the cochlea, passing the vibrations into the inner ear’s fluid.

Pressure Regulation

The ear connects to the mouth and sinus cavity through the eustachian tube.

When air pressure outside changes, pressure can build in the middle ear.

When we swallow or yawn, our ears will pop!

This is our eardrum shifting to release the pressure.

Protective Muscles

There are 2 muscles within the middle ear:

- Stapedius muscle

- Tensor tympani muscle

e.g., At a loud concert, these muscles tense up to reduce the energy passed along, protecting the delicate cochlea.

These muscles are also activated when we speak, slightly dampening the sound of our own voice.

Inner Ear

- Scala vestibuli (top chamber)

- Organ of Corti (middle layer): A delicate, specialised structure that transduces vibrations into neural signals.

- Scala tympani (bottom chamber)

Pressure Valves

For the cochlea to function, sound waves need a way in and a way out. Two small membranes act as pressure release valves.

- Oval Window: The stapes presses against this membrane, transmitting vibrations into the scala vestibuli and setting the cochlear fluid in motion.

- Round Window: A thin, flexible membrane at the other end of the cochlea. As fluid waves travel through the cochlea, the round window bulges outward to release the extra pressure.

Without the round window, the incompressible fluid of the cochlea would have nowhere to move, and the stapes wouldn’t be able to set up waves effectively.

Inside the Cochlea

The cochlea is set up to detect sounds at different frequencies.

Along its length runs the basilar membrane, which separates the scala vestibuli and scala timpani.

The basilar membrane isn’t uniform. Each section is tuned to a particular frequency, meaning it vibrates most strongly at that pitch. Mechanical properties determine which frequencies the basilar membrane is sensitive to.

In this way, the cochlea acts like a natural frequency analyser, translating the physical properties of sound into representative neural activity that the brain can interpret.

- High-frequency sounds (i.e birds chirping) create strong vibrations near the base of the cochlea, but fade quickly.

- Low-frequency (i.e. bass drum) travel further along the basilar membrane, peaking near the apex of the cochlea.

Inside the Organ of Corti

The answers lies in the Organ of Corti.

The Organ of Corti (as a reminder) is a delicate, specialised structure that sits on top of the basilar membrane.

- As fluid waves move through the cochlea, the basilar membrane vibrates up and down.

- Resting above it is the tectorial membrane, a gelatinous structure that does not move much in response to these waves.

Stereocilia are stiff, toothpick-like structures on hair cells that bend in response to vibration.

Hair Cells

- Outer hair cells: Their stereocilia are embedded in the tectorial membrane, so they are directly deflected as the basilar membrane moves.

- Inner hair cells: Their stereocilia float freely in the fluid. They respond to the overall fluid motion rather than direct contact.

Instead, they release neurotransmitters in a graded response, proportional to the frequency and amplitude of the incoming sound.

The first true neurons in this pathway are the spiral ganglion cells, which “listen” to the hair cells. Once activated, they fire action potentials and bundle their axons together to form the auditory nerve, carrying sound information to the brain.

Transduction

When hair cells are at rest, the basilar membrane is still and the stereocilia are upright. Only a few ion channels are open, so the cell sits near its resting potential.

Step 1: Deflection of Stereocilia

Each stereocilium is connected to its neighbour by tip-link proteins, so when one bends, the entire bundle shifts together.

- As the basilar membrane vibrates, stereocilia bend toward one direction, opening mechanically-gated potassium (K+) channels.

- When they bend the other way, the channels close.

Step 2: Ion Flow

Unlike in most of the central nervous system (CNS), the fluid around the hair cells — the endolymph — contains a high concentration of potassium.

Because the inside of the hair cell is relatively negative, positively charged ions are strongly driven to enter when channels open.

- The influx of K+ ions depolarises the cell.

- As the wave reverses, the channels close, and the cell becomes hyperpolarised again.

This rapid alternation encodes the timing and rhythm of the incoming sound wave.

Depolarisation opens voltage-gated calcium (Ca2+) channels.

- Ca2+ rushes in, triggering vesicles to fuse with the membrane.

- These vesicles release neurotransmitter onto the spiral ganglion cells.

The release is graded—always present at some level, but stronger or weaker depending on the frequency and intensity of the sound.

- Spiral ganglion cells listen to the graded messages of the hair cells and decide whether or not they will fire a binary action potential. They pass this chemical signal into the auditory nerve and onward to the brain.

Although both types of hair cells detect motion in the cochlea, they connect to spiral ganglion cells in very different ways.

- Many outer hair cells converge onto a single spiral ganglion cell. This means their information is pooled together before being passed on.

- Conversely, we have the opposite arrangement for inner hair cells. One inner hair cell communicates with many spiral ganglion cells. This spreads its information more widely through the pathway.

Outer hair cells actually outnumber inner hair cells 3:1.

Yet, most spiral ganglion cells are connected to inner hair cells. Only a small fraction listen to the outer ones.

This is because the two groups encode different aspects of sound.

- Inner hair cells: Specialised for frequency (pitch) detection.

- Outer hair cells: More sensitive to amplitude (volume) intensity.

e.g., It’s the change in pitch that lets us tell voices apart or identify a melody.

Hearing Loss

Broadly, hearing loss is divided into conductive deafness and sensorineural deafness.

Conductive Deafness

This occurs when sound waves are blocked from reaching the cochlea.

- Common causes: Ear infections, fluid buildup, damaged/calcification of the ossicles, or ruptured ear drum.

In these instances, mechanical vibrations cannot be transmitted effectively through the middle ear.

- Hearing aids are often effective here since they amplify incoming sound waves. Surgery may also help repair ossicles or eardrum damage.

This occurs when the cochlea or auditory nerve is damaged.

One of the most common causes is malfunctioning hair cells in the cochlea. In these cases, cochlear implants can help.

- A cochlear implant works by bypassing the damaged hair cells entirely.

It acts like an artificial basilar membrane, directly stimulating the auditory nerve with electrical signals instead of relying on mechanical-to-neural conversion.

- Auditory nerve damage: If the nerve itself is damaged, bypassing the hair cells is not enough, since the pathway to the brain is interrupted.

Sometimes both conductive and sensorineural components are present. For example, someone might have ossicle calcification and cochlear hair cell damage. Procedures may then involve a combination of surgery, hearing aids, or implants, depending on the primary cause.

Cochlear Amplification

On their surface, they contain a special protein called prestin, a voltage-sensitive motor protein.

How It Works

- When the hair cell depolarises, prestin contracts, pushing the cell against the tectorial membrane and boosting the effect of the vibration.

- When the hair cell hyperpolarises, prestin relaxes, allowing the cell to expand and pull away, further enhancing the contrast.

Why Does This Matter?

Cochlear amplification allows us to detect sounds at very low intensities that would otherwise be too faint to perceive.

It fine-tunes our sensitivity to quiet sounds and subtle differences in pitch.

Clinical note: The drug furosemide can inhibit prestin proteins, removing this amplification mechanism. As a result, the ear becomes less sensitive, particularly to low-intensity sounds.

Audition Pathway

Step I: Cochlear Nucleus

- At this stage, information is still unilateral.

e.g., input from the left cochlea comes from the left auditory nerve and hits the left ventral cochlear nucleus (and vice versa).

Step II: Superior Olives

- The cell in the central cochlear nucleus sends information to both the right and the left superior olives.

- The superior olives are a cluster of brainstem neurons that compare input from both ears to determine sound direction.

The ventral cochlear nucleus still only gets input from one side.

In contrast, the superior olive receives input from both ears, allowing it to compare signals.

- If a sound comes from the right, it reaches the right ear slightly earlier than the left.

- The superior olive detects this timing difference (~10-20 ms) and determines that the sound is closer to the right side of the body.

Other processes, like interaural intensity differences, help with front vs. back localisation.

Step 3: Inferior Colliculus

e.g., Turning your head toward a sudden noise

Step 4: Thalamus (MGN)

Step 5: Auditory Cortex (A1)

Tonotopy

Hair cells sitting at each point along the membrane inherit this tuning.

!Reminder!

- High-frequency sounds vibrate hair cells near the base.

- Low-frequency sounds vibrate hair cells near the apex.

This preserves the frequency-specific coding in A1.

- Posterior regions respond most strongly to high frequencies.

- Anterior regions respond most strongly to low frequencies.

If we were to record from a spiral ganglion cell, we would find that it has a “characteristic frequency” — the frequency at which it fires the most action potentials.

This allows the brain to map which frequencies are present in a sound, based on which spiral ganglion cells are active.

Together, this system creates a detailed representation of sound frequency, so that the brain can distinguish between pitches, voices, and complex auditory patterns.

A1 sorts sounds by frequency, timing, and pattern. But meaning comes from what happens next: connections to association areas like the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system. These connections allow us to recognise voices, understand language, and process music with memory and emotion.

BUT, that’s a story for another time...another series?

The Vestibular System

Unlike the cochlea, these structures don’t respond to sound. Instead, they detect movements of the head and make compensatory movements accordingly.

Each canal is oriented in a different plane:

Up/Down. Left/Right. Tilt/Rotation.

This is why there are three: together, they cover all possible directions of head movement.

Anatomy of the Vestibular System

The otolith organ includes the utricle and saccule. Inside are hair cells whose stereocilia extend into a gelatinous layer.

As the head moves, the jelly-like layer sloshes, bending the stereocilia back and forth.

- Otoconia: Tiny bio-crystals. They add weight to the jelly, helping couple mechanical forces to the hair cells. This makes them sensitive to linear acceleration and gravity.

- Kinocilium: The tallest of the hair bundles. Acts like a lever, amplifying the jelly’s motion and increasing sensitivity.

The vestibular system drives the Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex (VOR), which automatically adjusts our eye position when our head moves.

This keeps visual input steady on the retina so we can stay focused on objects even while moving.

- Sea sickness: Prolonged rocking motion on water, often worsened by poor visibility (e.g., fog).

- Air sickness: Vertical acceleration and tilting during flight, combined with limited visual cues.

- Car sickness: Sensory conflict between what the inner ear senses and what the eyes see, worsened by bumps and sharp turns.

Summary

- Sound waves are vibrations of compressed or spread-out air molecules that vary in frequency (pitch) and amplitude (volume).

- The outer ear funnels sound; the middle ear (ossicles) amplifies it; the inner ear (cochlea) converts it into fluid waves.

- The basilar membrane separates frequencies:

Base = high pitch;

Apex = low pitch

- Hair cells in the Organ of Corti transduce mechanical movement into electrical signals:

Outer hair cells = amplify (volume);

Inner hair cells = encode frequency (pitch)

- Spiral ganglion cells carry the signal as action potentials through the auditory nerve.

- Audition pathway: Cochlear nucleus; → Superior olive; (binaural comparison, localisation); → Inferior colliculus; → Thalamus (MGN); → Auditory cortex (A1).

- Tonotopy: Frequency map preserved from cochlea to cortex (low in anterior A1, high in posterior A1).

- Vestibular system: Semicircular canals + otolith organs detect head movement, acceleration, and gravity. Drives the VOR reflex to stabilise vision.

Key Terms

Below are definitions of common terms used throughout the volume.

Neurons

Neurons are the basic cells of the nervous system.

They send and receive information through electrical and chemical signals.

- Cell body (soma): The “hub” of the neuron. It contains the nucleus and all the usual cell machinery needed to stay alive.

- Neurite: A collective term to denote both axons and dendrites.

- Axons allow a neuron to pass information to other neurons.

Dendrites allow a neuron to receive information from other neurons.

These are the brain’s chemical messengers. They carry signals between neurons across the synapse (the tiny gap between cells).

When an action potential reaches the end of an axon, it triggers the release of neurotransmitters. These molecules cross the synapse and bind to receptors on the next neuron, influencing whether that cell will fire its own signal.

Different neurotransmitters have different effects: some excite (make a neuron more likely to fire), others inhibit (make it less likely).

Action Potential

A rapid electrical “spike” that neurons use to send information. It’s an all-or-nothing event: once the signal starts, it travels down the axon until it reaches the end of the cell, where it triggers the release of neurotransmitters.

An all or nothing approach is like flushing a toilet! You can either flush (have an action potential), or not flush (not have an action potential).

It doesn’t matter how hard/long you push the handle, same functionality applies.

Neurons maintain a difference in charge between the inside and outside of the cell. The inside is usually more negative than the outside (this is called the resting membrane potential).

Charged particles (ions) move according to gradients: positives are attracted to negatives, and vice versa. Uncharged particles follow different rules of diffusion, but this isn’t relevant here.

- Depolarisation: The inside becomes less negative (more positive) moving closer to the threshold needed to fire an action potential. This increases the likelihood that an action potential will occur.

- Hyperpolarisation: The inside becomes even more negative, moving further from the threshold. This reduces the chance that an action potential will occur.

These are proteins in the cell membrane that act like doors, opening or closing in response to physical movement. Unlike other forms of channels (chemical or voltage-gated), they don’t rely on signals or electricity — they move when the membrane itself is pushed, stretched, or bent.

In the ear, bending the tiny hair-like stereocilia physically pulls these channels open, letting ions rush in and starting the process of sound transduction.

These proteins open or close in response to changes in electrical charge across the cell membrane. They are triggered when the neuron becomes more or less electrically polarised.

When the voltage shifts past a certain threshold, these channels snap open, allowing ions—like sodium (Na⁺) or calcium (Ca²⁺) — to rush in. This sudden flow of charge helps generate or propagate an action potential.

Voltage-gated channels are essential for rapid signalling in the nervous system: they detect a change in electricity, respond instantly, and help carry messages along neurons at remarkable speeds. In the ear, these channels help convert the graded signals from hair cells into full electrical impulses that travel along the auditory nerve to the brain.

Why Do We Need Channels?

Because the cell membrane (made of a phospholipid bilayer) is naturally impermeable to charged particles like ions. Water and small uncharged molecules can slip through, but ions can’t cross on their own. Channels create the necessary “gates” for them to pass through.

Directional Terms

When describing the brain, we use special anatomical directions to keep things consistent.

e.g., the frontal lobe is anterior to the auditory cortex.

Posterior: Toward the back.

e.g., the cerebellum is posterior to the auditory cortex.

Dorsal: Toward the top.

e.g., In the brain, toward the top of the head.

Ventral: Toward the bottom.

e.g., In the brain, toward the base of the skull.

Medial: Toward the midline.

e.g., middle of the body/brain.

Lateral: Toward the sides.

e.g., your ears are lateral to your eyes.

Rostral: Toward the nose

(or front of the brain).

Caudal: Toward the tail

(or back of the brain).

Ipsilateral: Same side.

Contralateral: Opposite side.

e.g., The auditory cortex is superior to the brainstem.

Inferior: Below.

e.g., the brainstem is inferior to the auditory cortex.

Closing Remarks

These systems keep us grounded in the world and attuned to one another.

By peering more deeply into the ear, we gain another lens on perception itself: how the brain interprets vibration and motion in our daily lives.

My hope is that you see the elegance of neuroscience, and feel inspired to listen more closely (now that you know how to do it!) — to sound, to sensation, and to each other.

Stay tuned! The next neuroSense volume will turn from the ear to the eye, exploring how we perceive the world through sight.

thanks for reading!

amethyst